Byzantium, Constantinople, and Istanbul each have distinct cultural identities shaped by the eras and empires they embodied. They have inspired countless creators from Byzantine classical literature to Istanbul in popular culture.

Istanbul in Popular Culture and Literature – Table of Contents

Byzantium in Poetry & Literature

Byzantium, the ancient Greek colony founded in the 7th century B.C., is often evoked in classical and poetic imagination as a mystic threshold between East and West. Writers and poets who referred to Byzantium usually did so to evoke a sense of spiritual transcendence, imperial grandeur, or cultural twilight. William Butler Yeats immortalised the city’s spiritual and symbolic resonance in his poem Sailing to Byzantium, a metaphor for transcendent wisdom and artifice. For Yeats, Byzantium was not a mere place, but a timeless realm of the soul’s refinement, far removed from the transience of modern life.

Sailing to Byzantium by William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees

—Those dying generations—at their song,

The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect.

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence;

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

O sages standing in God’s holy fire

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing-masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

Audio file: Sailing to Byzantium by William Butler Yeats read by Dermot Crowley, November 2015.

Procopius, a 6th-century Byzantine historian, chronicled the city’s architecture and politics in works like The Buildings of Justinian, offering a detailed, almost reverent account of its imperial splendour. Later, historical novelists and essayists like Charles Maizières explored Byzantium’s role as a cultural and religious bridge, fascinated by its endurance and fall. For many, Byzantium was more than a place; it symbolised the tension between temporal power and timeless beauty, East and West, decay and transcendence.

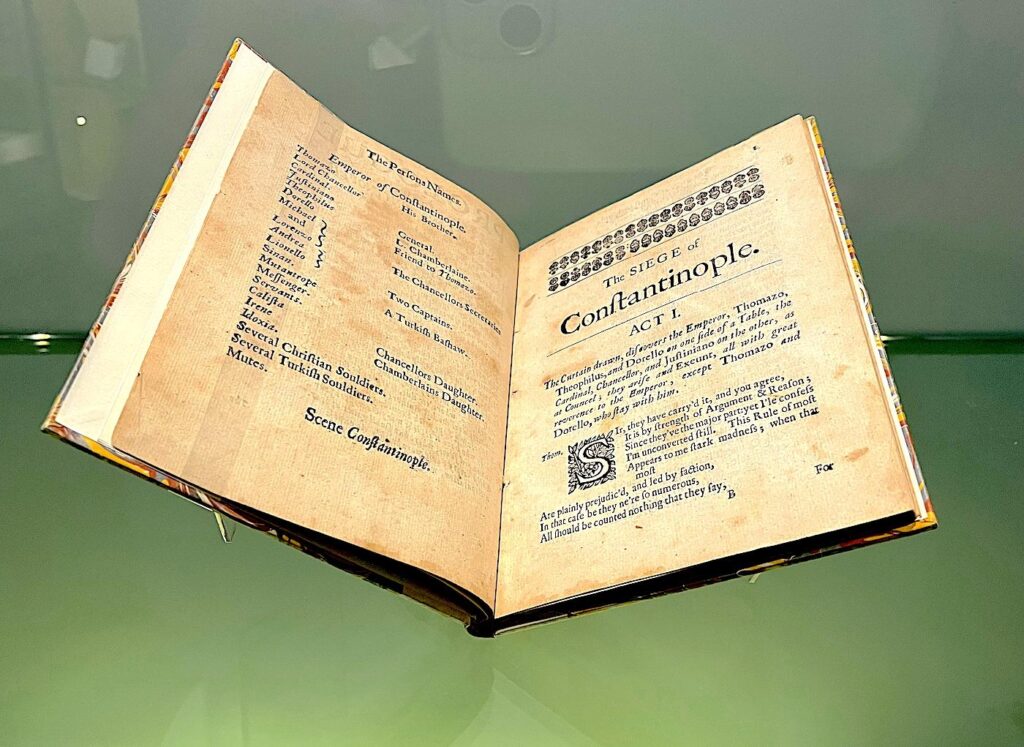

Constantinople in Literature

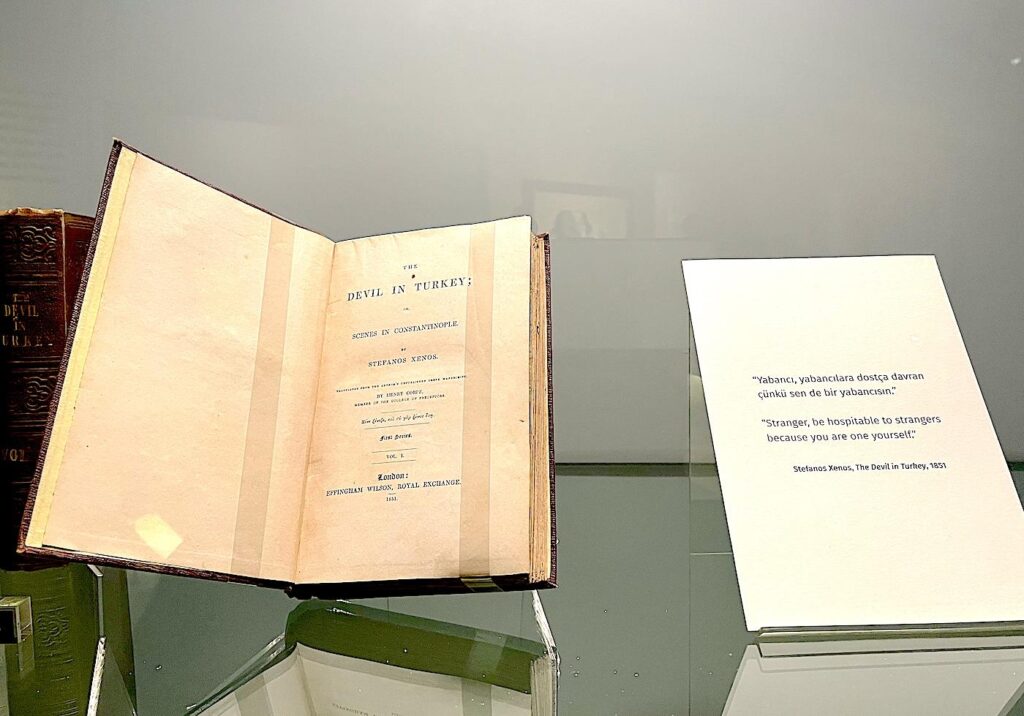

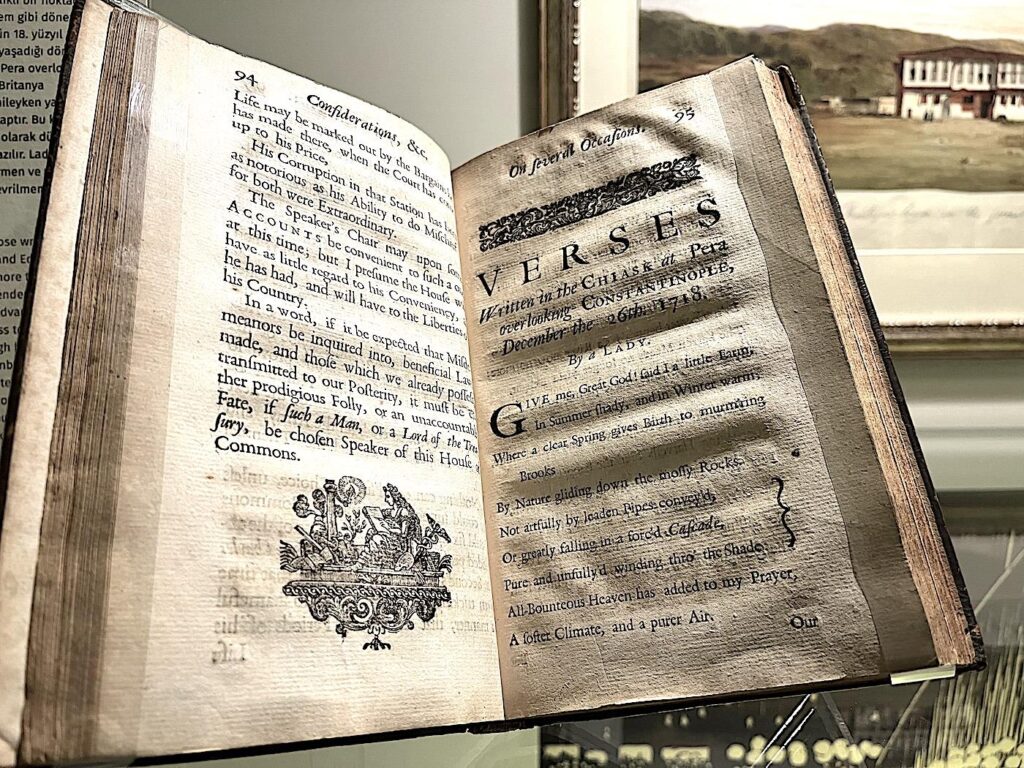

Constantinople, refounded in 330 A.D. by Emperor Constantine I, rapidly gained fame as the “New Rome.” It became a centre of Christian theology, imperial power, and cultural splendour. Medieval and Renaissance writers often described it as a city of mythical impenetrability and beauty. Stefanos Xenos, a Greek writer of the 19th century, depicted the city’s twilight in romantic yet sorrowful tones, lamenting the fall of Orthodox Christian rule. Travellers like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who lived in Constantinople in the early 18th century, wrote vivid, first-hand letters describing the customs of Ottoman high society, particularly the secluded world of women in harems, challenging the stereotypes of her contemporaries. These accounts gave Constantinople a human dimension often missed by male observers, adding depth to its cultural legacy.

In Ottoman and Islamic contexts, Constantinople took on new life as the capital of a vast, multicultural empire. While the name “Istanbul” was used colloquially by Turks even before the conquest, the city under Ottoman rule appeared in works like Evliya Çelebi’s Seyahatname and the poetry of Bâkî, often described with divine beauty and opulence.

Constantinople to Istanbul in Literature & Art

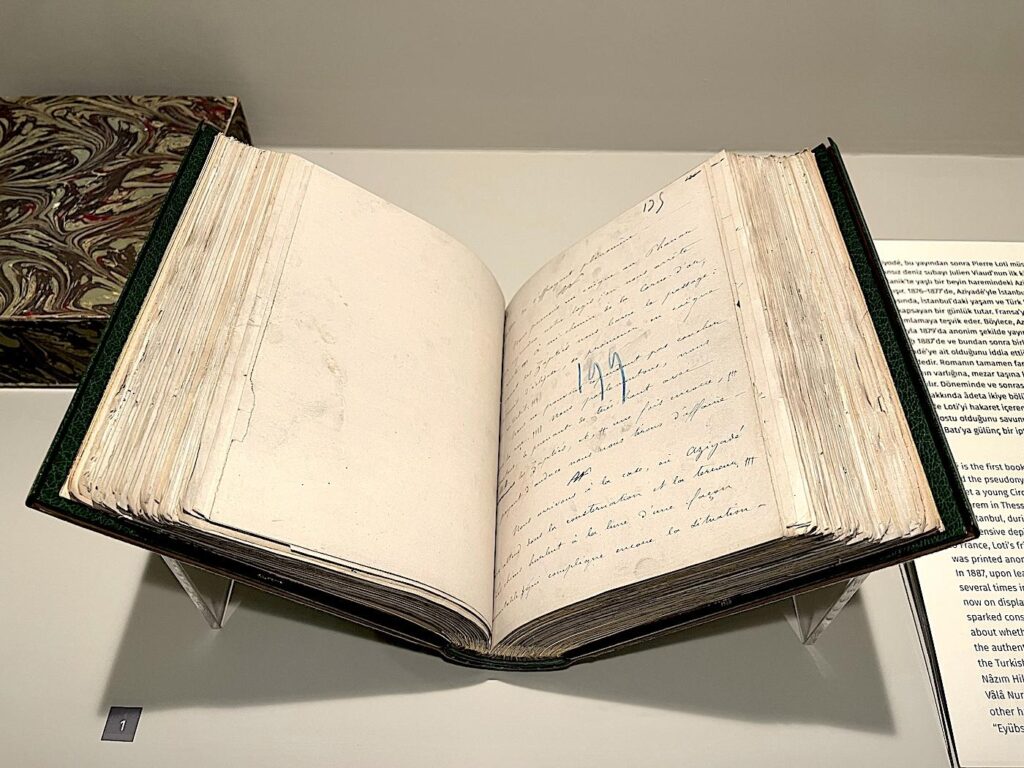

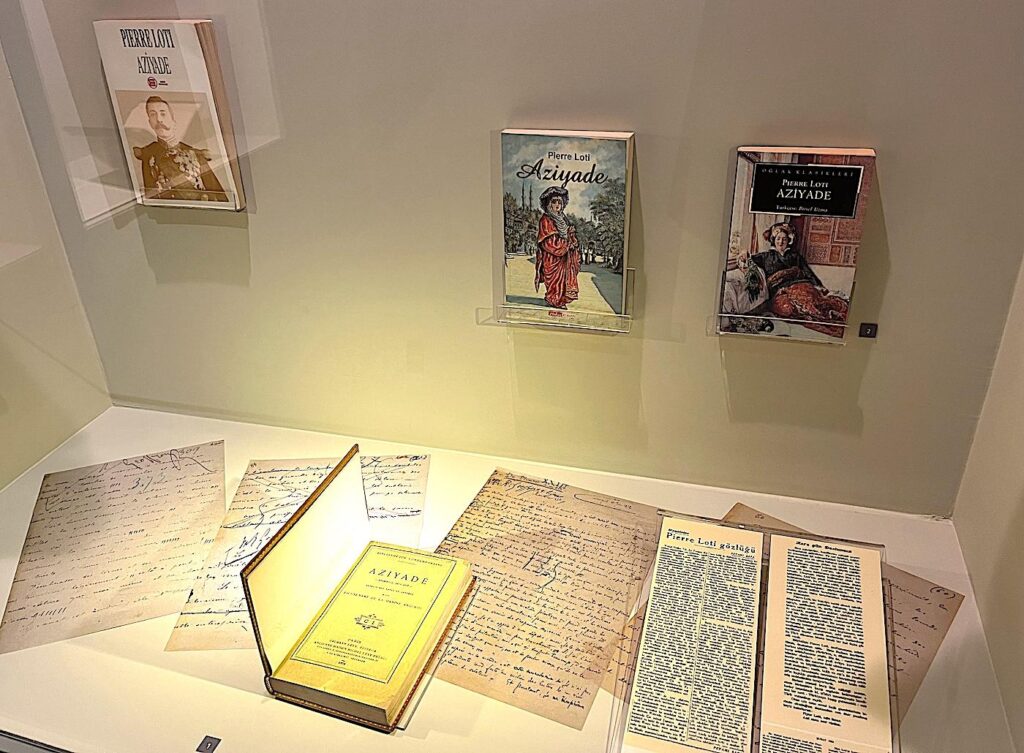

In the eyes of Western artists and travellers, the city became a locus of Orientalist fascination. Pierre Loti, a naval officer and novelist, famously romanticised Istanbul in his novel Aziyadé, an autobiographical tale of doomed love between a Frenchman and a harem woman.

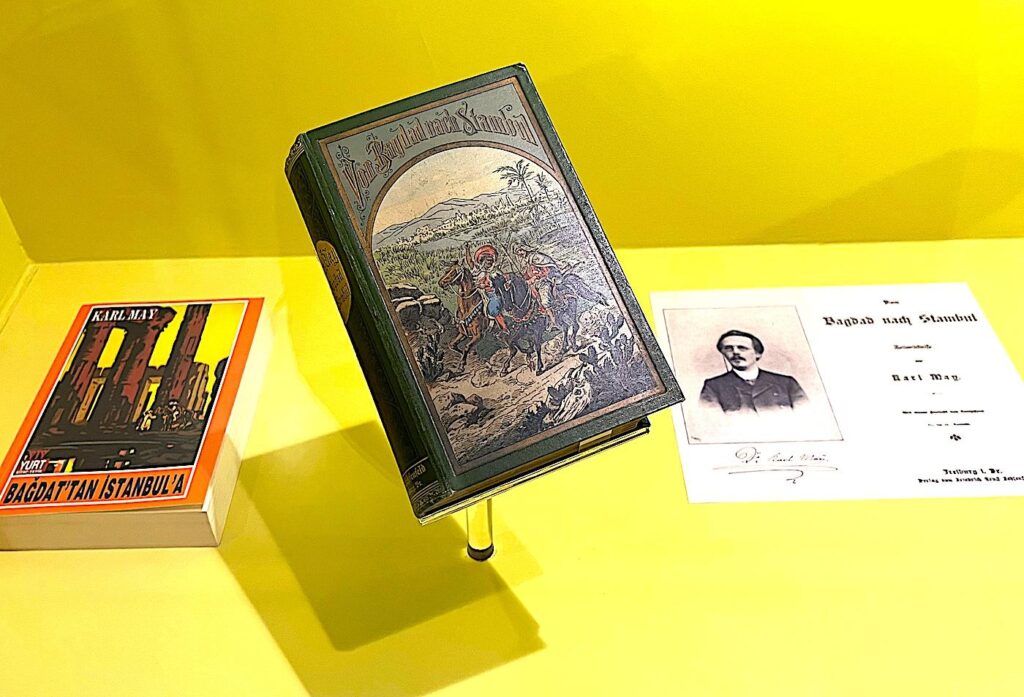

Meanwhile, painters like Edward Lear captured the Bosphorus and minarets in watercolours that blended travelogue and lyricism. Karl May, the prolific German adventure novelist, conjured up exoticised depictions of the Ottoman world for European audiences, often setting thrilling scenes in the shadowy quarters of Istanbul. Romantic, colonial, and sometimes problematic works cemented the city’s image in the European imagination.

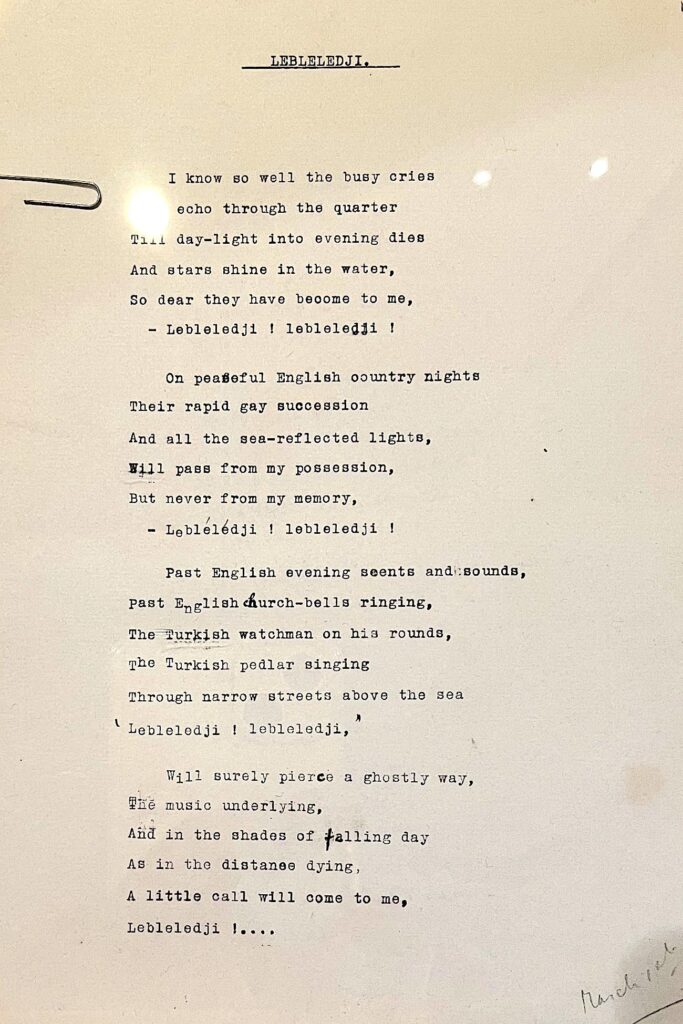

Constantinople – Leblebidji by Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962)

I know so well the busy cries

That echo through the quarter

Till day-light into evening dies

And stars shine in the water,

So dear they have become to me,

-Leblebedji! leblebedji!

On peaceful English country nights

Their rapid gay succession

And all the sea-reflected lights

Will pass from my possession,

But never from my memory,

– Leblebedji! leblebedji!

Past English evening scents and sounds,

Past English church-bells ringing,

The Turkish watchman on his rounds,

The Turkish pedlar singing

Through narrow streets above the sea

“Leblebedji! leblebedji,”

Will surely pierce a ghostly way,

The music underlying,

And in the shades of falling day

As in the distance dying,

A little call will come to me,

“Leblebedji!” ….

This evocative piece captures the poet’s nostalgic recollection of Istanbul’s nocturnal ambience, particularly the calls of the leblebedji, or roasted chickpea vendors, echoing through the city’s streets. The refrain “Lebleléaji! lebleledji!” mimics the vendors’ cries, embedding the sensory memory of Istanbul into the poem’s rhythm. Sackville-West juxtaposes these vibrant urban sounds with the tranquillity of the English countryside, highlighting the enduring impact of her experiences in Istanbul on her imagination.

In Poems of West & East, published in 1917, Vita Sackville-West explores themes of cultural contrast and personal reflection, drawing from her travels, including to Constantinople (Istanbul). Her poem “Leblebedji” leaves a lasting impression of the city on the poet’s psyche, blending auditory imagery with emotional resonance.

Throughout the 20th century, Turkish poets repeatedly turned to Istanbul as both muse and metaphor, capturing its shifting moods and timeless contradictions. Nazım Hikmet immortalised the city in many works. In Tell Me About Istanbul, Nâzım Hikmet evokes the city with tender nostalgia, while in The Walnut Tree, he uses the image of the tree in Gülhane Park to symbolise his belonging to Istanbul. Orhan Veli Kanık celebrated the city’s ordinary beauty in his minimalist, conversational poems, finding poetry in ferry rides, street vendors, and rain-soaked sidewalks. Yahya Kemal Beyatlı gave voice to a nostalgic, Ottoman-inflected Istanbul, particularly in Süleymaniye’de Bayram Sabahı, where the city’s spiritual and architectural grandeur shines. Attilâ İlhan, with noir-like intensity, painted Istanbul as both a romantic and political landscape, while İlhan Berk transformed it into a surreal, mythical city layered with time and language.

Walnut Tree (Ceviz Ağacı) by Nâzım Hikmet

Başım köpük köpük bulut, içim dışım deniz,

ben bir ceviz ağacıyım Gülhane Parkı'nda,

budak budak, şerham şerham ihtiyar bir ceviz.

Ne sen bunun farkındasın, ne polis farkında.

Foamlike clouds my head,

the sea is me inside and out,

a walnut tree I am, in Gülhane Park:

an old walnut tree, gnarled and scarred.

This, neither you notice, nor the police.

Ben bir ceviz ağacıyım Gülhane Parkı'nda.

Yapraklarım suda balık gibi kıvıl kıvıl.

Yapraklarım ipek mendil gibi tiril tiril,

koparıver, gözlerinin, gülüm, yaşını sil.

Yapraklarım ellerimdir, tam yüz bin elim var.

Yüz bin elle dokunurum sana, İstanbul'a.

Yapraklarım gözlerimdir, şaşarak bakarım.

Ben bir ceviz ağacıyım Gülhane Parkı'nda.

Ne sen bunun farkındasın, ne polis farkında.

I am a walnut tree in Gülhane Park.

My leaves sparkle like fish in water.

My leaves flutter like silk handkerchiefs;

pick a few, sweetheart, and wipe your tears.

My leaves are my hands; I have one hundred thousand hands.

I touch you, Istanbul, with one hundred thousand hands.

My leaves are my eyes, I look in wonder.

I watch you, Istanbul, with one hundred thousand eyes…

And my leaves beat, like one hundred thousand hearts.

Yüz bin gözle seyrederim seni, İstanbul'u.

Yüz bin yürek gibi çarpar, çarpar yapraklarım.

I am walnut tree in Gülhane Park,

this, neither you notice, nor the police.

1 July 1957

Translated by: Cahit Baylav

Istanbul in Popular Culture

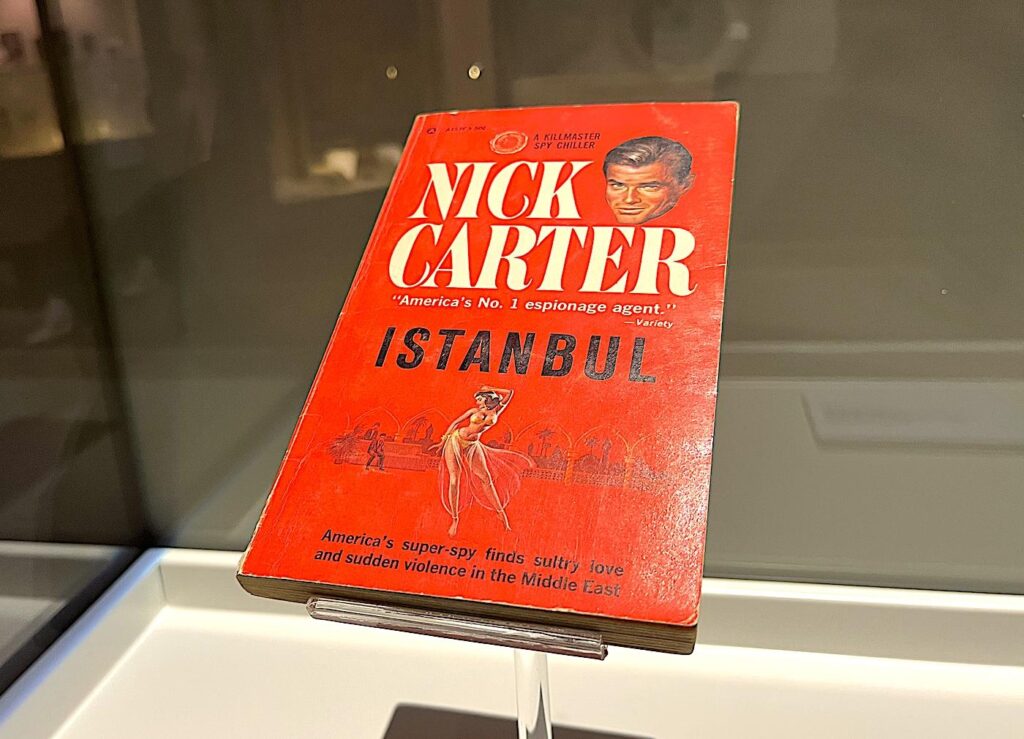

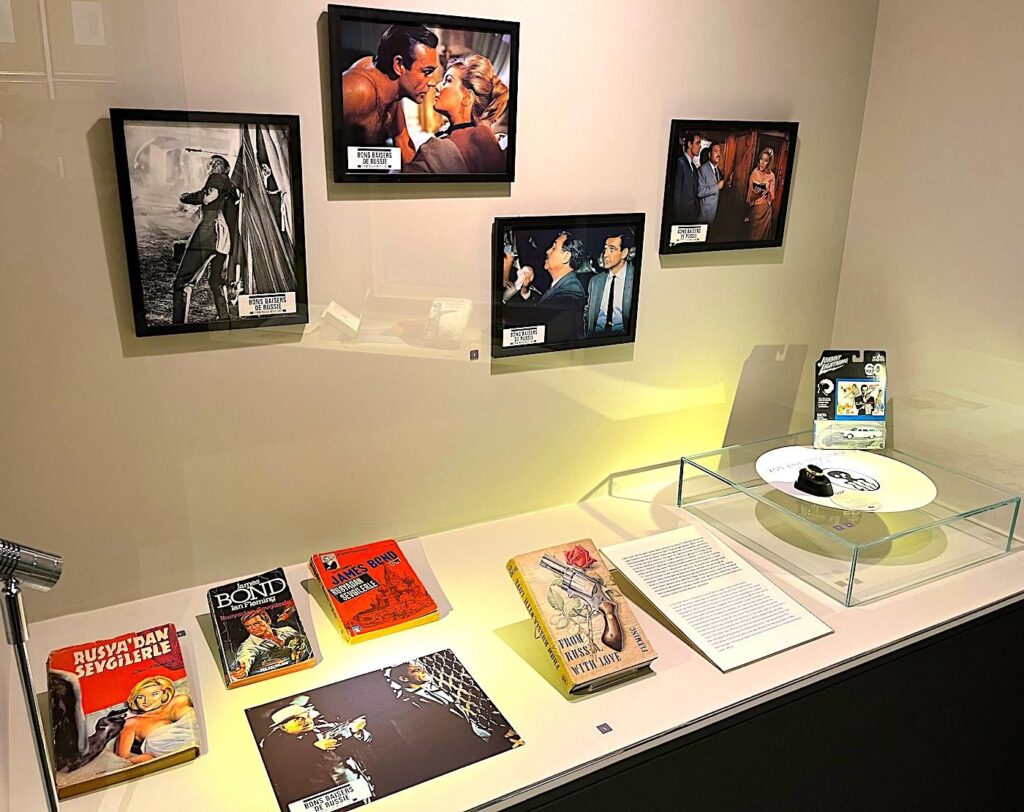

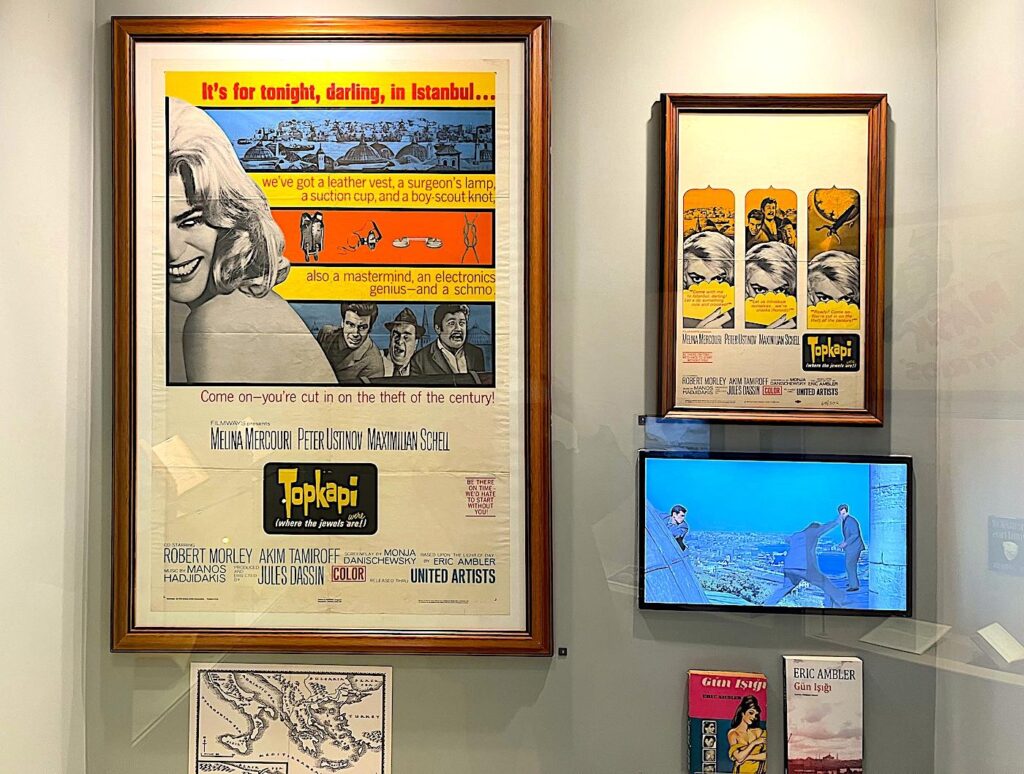

In modern popular culture, Istanbul is a city of intrigue, drama, and romance. In film, the city’s ancient walls and bustling bazaars have provided an atmospheric backdrop. They are a favourite setting in spy thrillers and action films like From Russia with Love and Taken 2, where their maze-like streets and East-meets-West geography provide exotic tension. In From Russia, With Love, James Bond navigates espionage through cisterns and mosques, and in Topkapi, a heist movie centred on a slapstick caper in the iconic Topkapı Palace. Agatha Christie wrote parts of Murder on the Orient Express while staying at the Pera Palace Hotel in Istanbul. Graham Greene used the city’s tangled politics and noir ambience in his espionage novels. Even pulp fiction got its turn: spy hero Nick Carter dashed through Istanbul’s alleyways in mid-century paperbacks, chased by shadows of the Cold War and the Ottoman past.

In video games like Assassin’s Creed: Revelations, the city becomes a fully realised historical landscape for exploration and intrigue. Constantinople is the central setting, portrayed in rich historical detail during the early 16th century under Ottoman rule. The game immerses players in the city’s diverse districts, from the bustling Grand Bazaar and majestic Hagia Sophia to the rooftops of Galata, blending real-world architecture with the series’ signature parkour and stealth mechanics.

In Turkish popular culture, Istanbul is portrayed as a city of deep contrasts, where tradition meets modernity, and melancholy dances with vibrant energy. It is the backdrop of countless Turkish films, TV dramas, songs, and novels, often depicted as a character in its own right. In cinema, directors like Nuri Bilge Ceylan and Ferzan Özpetek explore its moody beauty and complex social fabric, while in literature, authors like Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak reflect on its layered identity, from Ottoman shadows to secular modernism. The Bosphorus, ferries, street vendors, and changing skylines are scenery and emotional anchors in the Turkish collective imagination, a city forever caught between memory and change.

Istanbul in Classical & Popular Music

Byzantium, Constantinople, and Istanbul have inspired musical interpretations by composers and contemporary artists. Benjamin Britten referenced Byzantium in his composition “Nocturne” Op. 60 (1958), a song cycle for tenor, seven obbligato instruments, and strings. The final movement of this work sets William Butler Yeats’s poem “Byzantium” to music. The city carries an aura of mystical allure and lost grandeur that surfaces in classical compositions, gothic rock, and ambient electronic music, where it’s used to suggest ancient wisdom and spiritual escape.

In contrast, Constantinople and Istanbul have found more playful and widespread expression in 20th and 21st-century pop culture. The catchy novelty song “Istanbul (Not Constantinople),” first recorded by The Four Lads in 1953 and later popularised by They Might Be Giants, cleverly riffs on the city’s changing identity, embedding its historical transformation into mainstream consciousness.

Istanbul (Not Constantinople) Lyrics by Jimmy Kennedy

Istanbul was Constantinople

Now it’s Istanbul, not Constantinople

Been a long time gone, Constantinople

Now it’s Turkish delight on a moonlit night

(Oh) every gal in Constantinople

(Oh) lives in Istanbul, not Constantinople

(Oh) so if you’ve a date in Constantinople

(Oh) she’ll be waiting in Istanbul

Even old New York

Was once New Amsterdam

Why they changed it I can’t say

People just liked it better that way

So take me back to Constantinople

No, you can’t go back to Constantinople

Been a long time gone, Constantinople

Why did Constantinople get the works?

That’s nobody’s business but the Turks’

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo / ohhhhhhh ohh ohh ohh

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo / ohhhhhh ohh ohh ohh

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo / ohhhh ohh ohh ohh ohhh

Istanbul (Istanbul)

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo / ohhhhhhh ohh ohh ohh

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo / ohhhhhhh ohh ohh ohh

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo / ohhhh ohh ohh ohh ohhh

Istanbul (Istanbul)

Even old New York

Was once New Amsterdam

Why they changed it I can’t say

People just liked it better that way

Istanbul was Constantinople

Now it’s Istanbul, not Constantinople

Been a long time gone, Constantinople

Why did Constantinople get the works?

That’s nobody’s business but the Turks’

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo

Doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo doo doo doo

Doo doo doo doo doo doo doo doo

So take me back to Constantinople

No, you can’t go back to Constantinople

Been a long time gone, Constantinople

Why did Constantinople get the works?

That’s nobody’s business but the Turks’

Istanbul

Istanbul has been a central muse for Turkish pop musicians, often portrayed as a city of longing, heartbreak, and layered beauty. Sezen Aksu frequently evokes Istanbul in her songs as both a backdrop and a metaphor for emotional turmoil and resilience. In tracks like İstanbul Hatırası and Kavaklar, she captures the city’s bittersweet spirit, romantic fog, restless nights, and role as a silent witness to countless love stories. Other artists like Tarkan, Teoman, and Mor ve Ötesi also weave Istanbul into their lyrics, highlighting the city’s chaotic charm and existential melancholy. Whether through nostalgic ballads or energetic pop anthems, Istanbul emerges in Turkish music as a setting and complex character.

Ultimately, Byzantium, Constantinople, and Istanbul are far more than successive names; they are symbolic incarnations of a single city’s evolving soul. From Yeats’s mystical vision of Byzantium to the comic intrigue of Topkapi, from Lady Mary Montagu’s sharp-eyed letters to the wistful passion of Pierre Loti’s Aziyadé, and from the aching sorrow in Sezen Aksu’s lyrics to the tension-laced glamour of spy thrillers, the city lives on as a perennial muse. Istanbul, straddling two continents and countless epochs, remains one of the world’s most storied and resonant cultural icons, a place where memory clings to alleyways, myths echo through minarets, and history breathes in every stone.

See also – LikeTürkiye.com – Top 10 Istanbul Art Galleries – Meşher Art Gallery.