The Istanbul Tulip Festival is a vibrant celebration of spring and a tribute to the tulip’s deep cultural significance in Turkish history. The city bursts into colour each April as millions of tulips bloom across public spaces, turning Istanbul into a living canvas of floral art. Although commonly associated with the Netherlands, the tulip has its origins in the Ottoman Empire, where it was a symbol of elegance and abundance, especially during the “Tulip Era” (Lâle Devri) of the 18th century.

Istanbul Tulips – Table of Contents

When to see the Istanbul Tulip Festival

The festival typically occurs throughout April, ideally early/mid-April when the tulips are in full bloom. The Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality organises the event annually, planting over 30 million tulips in a stunning array of colours and varieties. Each year brings new floral designs and arrangements, often forming massive flower carpets, intricate patterns, or even depictions of famous Turkish motifs. The festival draws locals and tourists worldwide to witness this spectacular display of nature and artistry.

Weather and environmental factors play a crucial role in when tulips bloom. Tulips require a period of cold dormancy to flower correctly, so they are planted in the autumn. During the winter, the frigid temperatures trigger biochemical processes within the bulbs necessary for healthy growth. If the winter is too mild or short, tulips may not bloom as robustly or might have delayed and uneven flowering. On the other hand, a very harsh or prolonged winter can damage bulbs or delay blooming well into the spring. Soil temperature is also essential; tulips generally emerge when the soil warms to around 7–10°C.

In spring, tulips are sensitive to fluctuations in temperature and rainfall. A sudden heatwave can cause tulips to bloom earlier than usual and shorten their flowering period, as high temperatures speed up the plant’s lifecycle. Likewise, strong winds or heavy rain can damage the delicate blooms. Ideal blooming conditions include moderate spring temperatures, sunshine, and well-drained soil. Urban microclimates, elevation, and even the direction a park or garden faces can also influence bloom timing slightly. This is why different parks in a city like Istanbul may see tulips bloom at slightly different times, even during the same festival.

See also: LikeTürkiye.com – Weather & Climate

Where to see the Istanbul Tulip Festival

Some of the best places to experience the Tulip Festival in Istanbul include Emirgan Park, Gülhane Park, Yıldız Park, Sultanahmet Square, and Camlica Hill. Emirgan Park, located along the Bosphorus in the Sarıyer district, is the festival’s centrepiece and features some of the most elaborate displays. Gülhane Park, near Topkapı Palace, offers a more historical backdrop, while Yıldız Park, nestled between Beşiktaş and Ortaköy, offers beautiful walking paths lined with tulips. Sultanahmet Square provides a more central location, with tulips blooming beneath the minarets of the Blue Mosque, creating postcard-perfect views.

| Park | Region | Map Location |

|---|---|---|

| Emirgan Park | Sarıyer (north) | Map Location |

| Gülhane Park | Fatih (centre) | Map Location |

| Yıldız Park | Beşiktaş (centre) | Map Location |

| Sultanahmet Square | Fatih (centre) | Map Location |

| Camlica Hill | Üsküdar (Asian side) | Map Location |

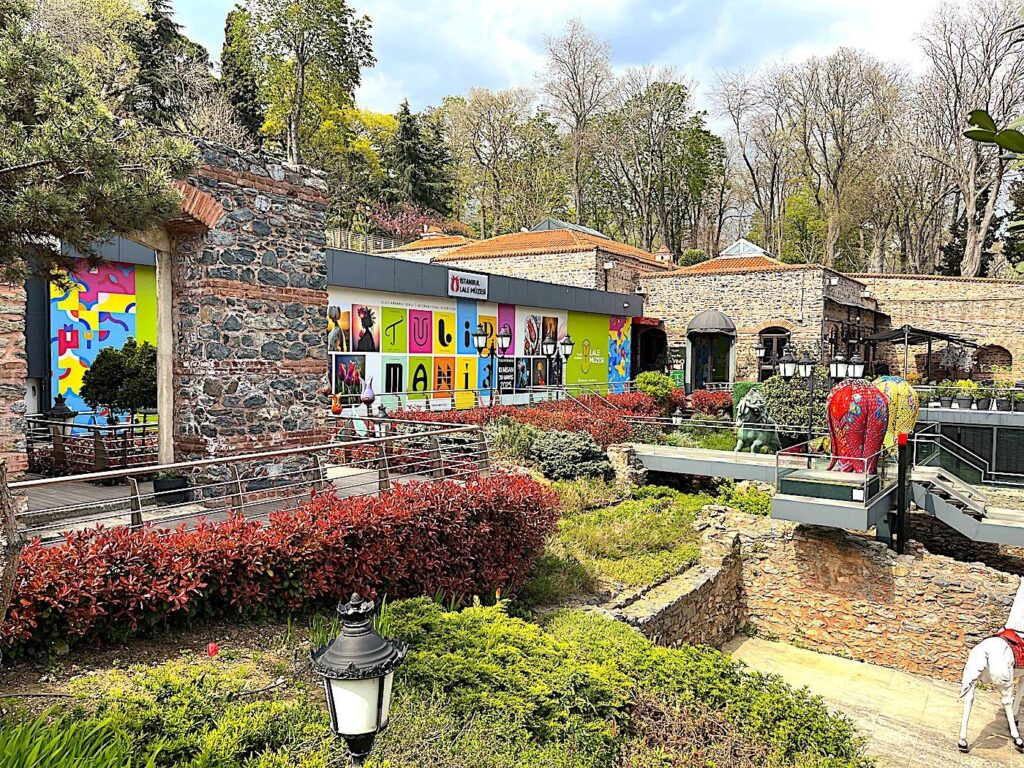

Istanbul Tulip Museum (Lale Müzesi)

Location: Lale Müzesi, Emirgan, Koruyolu Cd. No. 1, 34467 Sarıyer/İstanbul, Türkiye Note, the museum entrance from Emirgan Park’s southeast corner was closed in April 2025 – Website: Official Museum Website (English) – Opening Times: 10:00-20:00. Ticket Price: As at April 2025, the Turkish Lira equivalent of €2.50 for the Tulip museum and €6.00 including the temporary Leonardo da Vinci exhibition.

The İstanbul Lale Müzesi, or Istanbul Tulip Museum, is a cultural institution dedicated to celebrating and preserving the rich heritage of tulips in Türkiye. Established by the Istanbul Tulip Foundation (İstanbul Lale Vakfı), the museum is located on the southeast corner of the scenic Emirgan Park in the Sarıyer district of Istanbul, close to the Sakıp Sabancı Museum. This location is significant, as Emirgan Park is renowned for its extensive tulip gardens, especially during the annual Istanbul Tulip Festival. The museum’s initial aims were to educate visitors about the historical and cultural significance of tulips, which have been an integral part of Turkish art and tradition since their introduction from Central Asia in the 16th century.

The museum features two main exhibition halls, the left hall houses a modest permanent ethnographic collection of tulips-related artefacts. The exhibition includes a small collection of garments and fabrics adorned with tulip motifs, ceramics, artworks and decorative items featuring tulips. In the right hall is a temporary exhibition that is more extensive than the tulip ethnographic exhibition. Until summer 2025, it features the works of Leonardo da Vinci. Prior temporary exhibitions have featured Andy Warhol -Pop Talk (winter 2023/4), Ali Bakova, curator – Tulip Mania (spring 2024), and İsmail Yiğit, tilemaster – The Tulip and Tile Dance Exhibition (summer 2024).

In addition to these exhibits, the museum includes a photo gallery, conference rooms, a library, and open-air exhibition spaces. The museum serves as a hub for cultural and educational activities, offering interactive training activities, workshops, seminars, and seasonal exhibitions to engage the public and promote the ongoing appreciation of this iconic flower. On the museum’s right (north) side is a reasonably priced café with a terrace with views of the Bosphorus.

The History of Istanbul Tulips

The history of the tulip begins in the wild mountainous regions of Central Asia, particularly in present-day Kazakhstan and the Tien Shan mountains. The Turks first cultivated these hardy flowers as early as the 10th century. The name “tulip” is believed to come from the Persian word dulband, meaning turban, likely due to the flower’s resemblance to the shape of a wrapped turban. Tulips were eventually brought westward to the Ottoman Empire, gaining immense popularity, especially during the 16th century under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

In the Ottoman Empire, tulips symbolised power, wealth, and refinement. They were meticulously cultivated in palace gardens and featured prominently in Ottoman poetry, textiles, tiles, and miniature paintings. The 18th century saw the height of tulip obsession in Istanbul during the so-called Tulip Era (Lâle Devri), a time of peace and cultural flourishing under Sultan Ahmed III. Tulips were admired not just for their beauty but also for the elegance they represented. Garden parties and night-time tulip viewings by lantern light became fashionable among the elite, and the flower was celebrated as a symbol of abundance and good taste.

Tulips made their way to Europe in the mid-1500s, primarily due to the efforts of diplomats and botanists who encountered the flower in the Ottoman courts. The most famous of these was Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, the Austrian ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, who is credited with introducing tulip bulbs to Europe. From there, they spread quickly, especially in the Netherlands, where they became the centerpiece of a speculative frenzy known as “Tulip Mania” in the 1630s. During this time, rare tulip bulbs were sold for extraordinarily high prices, sometimes costing more than a house, before the market eventually collapsed.

Despite their economic ups and downs, tulips retained their charm and continued to be cultivated and hybridised into the hundreds of varieties we see today. While the Dutch are now globally associated with tulip farming and export, the flower’s spiritual and cultural home remains deeply rooted in Turkish history. The tulip remains a national symbol in modern Türkiye, representing beauty, resilience, and a golden age of creativity. The annual Tulip Festival in Istanbul is a contemporary celebration and a tribute to this long and fascinating journey.

Tulip Mania 1630s-1637

Tulip Mania was a period during the 1630s in the Dutch Republic when the prices of tulip bulbs skyrocketed to astonishing levels before suddenly collapsing in February 1637. It is widely considered the first recorded economic bubble in history. The Ottoman Empire introduced Tulips to Europe in the mid-16th century and became a luxury item among the Dutch elite. As rare and uniquely patterned tulips (often due to a virus-induced colour-breaking) grew in popularity, speculators began trading bulbs not just as flowers, but as high-value commodities, sometimes for the price of a house or more. This speculative frenzy detached tulip prices from their real value, leading to a crash that devastated many who had invested heavily.

The Ottomans had cultivated tulips for centuries before they caught the attention of European botanists and merchants. The distinctive “broken” tulips, those with variegated flame-like streaks, were especially prized, though unknown at the time, these patterns were caused by the Tulip Breaking Virus (TBV). Ironically, the same virus that made tulips so desirable also made them less stable to grow, contributing to each bulb’s unpredictability and speculative value. Today, “Tulip Mania” is a metaphor for speculative economic bubbles where asset prices are driven far above intrinsic value by hype, only to crash when reality sets in, parallels often drawn with phenomena like the dot-com bubble, cryptocurrency surges, or housing market crashes.

The Tulip Era (Lâle Devri) – 1718-1730

The Tulip Era (Lâle Devri) was a distinctive period in Ottoman history, spanning roughly from 1718 to 1730, during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III and the grand vizier Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha. This era followed the Treaty of Passarowitz, which brought a temporary peace between the Ottoman Empire and European powers. During this time, the Ottoman elite shifted their focus from military conquests to art, culture, architecture, and leisure. The name “Tulip Era” stems from the extraordinary fascination with tulips among the ruling class; these flowers became symbols of refinement, wealth, and a cosmopolitan lifestyle. Tulip cultivation peaked, and vast gardens full of exotic tulip varieties were planted throughout Istanbul, especially in places like Emirgan, Yıldız, and Topkapı Palace.

Culturally, the Tulip Era marked the beginnings of modernisation and Western influence in Ottoman society. Printing presses were introduced, public architecture flourished, and coffeehouses and garden parties became centers of intellectual and artistic life. Tulips, imported and bred in a variety of stunning forms, were displayed in elaborate floral arrangements and celebrated in poetry, miniature art, and textiles. The flower became an aesthetic ideal, representing the delicate balance between beauty and impermanence. However, this indulgence and extravagance eventually sparked discontent among the broader population. It ended abruptly in 1730 with the Patrona Halil Rebellion, which overthrew Ahmed III and marked a return to more conservative rule.

The Tulip and Sufism

In Sufism, the tulip holds symbolic meaning tied to themes of divine love, unity, and the mystical journey toward God. One of the most profound associations comes from the Turkish word for tulip, “lale,” which shares the same Arabic letters as “Allah” (الله) when written in Ottoman Turkish script. This connection has made the tulip a subtle yet powerful emblem of the divine. For Sufis, whose path centers on inner purification and union with the Beloved (God), the tulip’s elegant and upright form, its solitary beauty and quiet grace, mirrors the soul’s yearning for the divine and the noble simplicity of surrender.

The red tulip, in particular, has been linked to martyrdom and passionate love in Sufi poetry and iconography. The flower’s red petals are often seen as a metaphor for the lover’s heart, bleeding with longing for the Divine. Unlike more extravagant blooms, the tulip’s symmetrical and modest form reflects Sufi values such as humility and inward depth over outward display. In the Ottoman era, tulips were often used in calligraphy and dervish lodge decorations as a visual and spiritual symbol. This blend of nature and mysticism illustrates the Sufi understanding that every element of creation, when viewed with the eye of the heart, points back to the Creator.